Cecil Fielder had a pretty meandering baseball career. He broke in with the Blue Jays in 1985 and went up and down as a spare player from 1985-88. Cecil then played a season in Japan, hitting 38 home runs with the Hanshin Tigers in 1989. Fielder returned to MLB in 1990 and was an instant star with the Tigers, the Detroit version. He led baseball with 51 homers in 1990 and again with 44 homers in 1991.

Fielder was the proverbial star on a bad team in the early-1990s. He mashed 160 home runs from 1990-93 and the Tigers never made it closer than seven games out of a playoff spot. They were bad and getting worst. Detroit went 53-62 in 1994, 60-84 in 1995, and 53-109 in 1996. Fielder was now in his 30s and his game was starting slip, though he still had plenty of power.

The Yankees in 1996 needed more power. They went into the All-Star break with the best record in the AL (52-33) and a six-game lead in the AL East that year. They ranked 11th out of the 14 AL teams with 442 runs though, and their 74 home runs were the fourth fewest in all of MLB. On top of that, their 103 OPS+ against lefties was eighth out of those 14 AL teams. The Yankees went 13-15 against lefty starters in the first half.

Despite having the best record in the league, the Yankees had an obvious need for some more offense, particularly right-handed power. So, at the trade deadline, GM Bob Watson pulled the trigger on a blockbuster, acquiring Fielder from the Tigers for Ruben Sierra and top prospect Matt Drews. The plan was to install Fielder as the regular DH and move Darryl Strawberry to left field. The Yankees had seen Fielder make Yankee Stadium look small. They knew what he could do.

Sierra, a switch-hitter, was expected to give the Yankees some lineup balance and power, but it didn’t happen. He hit .258/.327/.403 (83 OPS+) with eleven homers in 96 games with New York before the trade, and he accused Torre of lying about playing time earlier in the season. Torre took the high road, telling reporters, “(Ruben) tried, but he just wasn’t the home run threat we needed.”

Sierra was included in the trade to essentially clear a roster spot and help even out the salary. He was making $6.2M that season while Fielder was making $9.2M. To help facilitate the trade, Fielder agreed to defer $2M of his 1997 salary. The Yankees ended up paying Fielder $7.56M from 1996-97 while the Tigers paid Sierra $7.14M during that same time. New York’s payroll rose ever so slightly.

The key to the trade was Drews, the Yankees’ first round pick (13th overall) in the 1993 draft. He was a significant prospect. Baseball America ranked Drews as the 12th best prospect in baseball heading into the 1996 season — fifth best pitching prospect behind Paul Wilson, Alan Benes, Livan Hernandez, and Jason Schmidt — and the Yankees skipped the 21-year-old righty over Double-A and had him start 1996 in Triple-A.

Drews struggled big time during that 1996 season though — he had a 6.00 ERA with 72 walks and 56 strikeouts in 84 innings before the trade, including 27 walks and seven strikeouts in 20.1 Triple-A innings — which is why the Yankees were willing to give him up. I wonder how that would have gone over nowadays. Drews went into the season as an elite prospect, struggled, then was traded for an aging one-dimensional slugger. I imagine that deal would have been branded “selling low” and gone over poorly 2016.

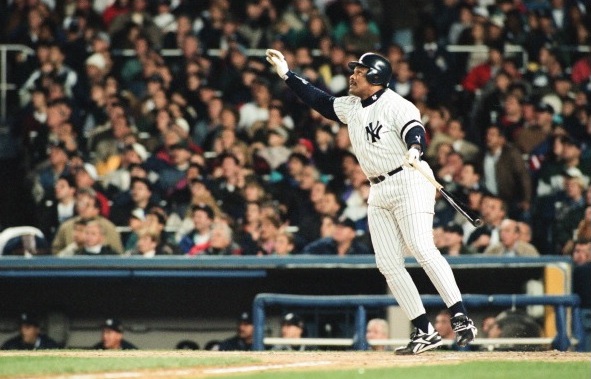

Anyway, the trade was made. Big Daddy Cecil Fielder was a Yankee and he couldn’t have been happier. “This is weird, but I’m going to work for the Yankees,” said Fielder to Curry. ”I’m going to enjoy myself. This feels great. I’m relaxed and I want to help the team. This is an opportunity for me to finally get in the hunt … I didn’t think it would be the Yankees. That’s a good place. I’m happy to be getting this opportunity.”

Torre installed Fielder as his regular DH and cleanup hitter immediately. That cleanup spot had been a revolving door much of the season — Strawberry, Sierra, Tino Martinez, and Bernie Williams all took turns hitting fourth behind Paul O’Neill — but Fielder came in and started 28 straight games and 41 of 42 games as the No. 4 hitter following the trade. He gave the Yankees the lineup stability they were lacking.

At the time of the trade Fielder was hitting .248/.354/.478 (109 OPS+) with 26 homers in 107 games for the Tigers. There was some concern he would disrupt the Yankees’ clubhouse chemistry because he was a superstar and one of the highest paid players in baseball, but that never happened. Fielder fit right in. His goal was to win after spending all those years on the non-contending Tigers clubs. It was a seamless integration into the clubhouse.

Of course, it helped that Fielder delivered. The Yankees struggled a bit in the second half and Fielder was their rock offensively, hitting .260/.342/.495 (108 OPS+) with 13 home runs in 52 games. He went deep in his second game in pinstripes, then again in his third, then again in his ninth and 11th. In early-September, when the Yankees were trying to hold off the surging Orioles, Fielder hit .250/.391/.536 with five homers, 12 walks, and ten strikeouts in a 16-game span. He drove in 15 runs.

Once back in the postseason — Fielder got three at-bats in the 1985 ALCS with the Blue Jays — Fielder stepped up his game and became a force. He hit .364 with a home run and drove in four runs in the team’s ALDS win over the Rangers. His seventh inning RBI single in Game Four proved to be the series-clinching run. Fielder had two homers and drove in eight runs in the five ALCS games against the Orioles. He drove in three insurance runs with a dinger in the Game Five clincher.

The World Series potentially posed a challenge to Torre because they weren’t going to have the DH in the NL park, yet they clearly needed Fielder’s bat in the lineup. Tino made that decision easy though — he went 9-for-44 (.205) in the team’s first eleven postseason games, so Torre put Fielder at first base when the series shifted to Atlanta. Martinez came off the bench for defense late.

Big Daddy went 1-for-3 with a walk in the Game Three win in Atlanta. He went 2-for-4 with a walk in Game Four, and started the Yankees’ comeback rally by driving in their first two runs of the game with sixth inning single. The Yankees were down 6-0 at the time. Then, in Game Five, that classic Andy Pettitte-John Smoltz duel, Fielder had three of his club’s four hits, including a fourth inning RBI double that drove in the only run of the game.

The 1996 Yankees were a very good team with some flaws. They were not a great offensive club and they lacked power, especially against left-handed pitchers. Watson identified that flaw, recognized his team had a chance to do something special, and went out and acquired Fielder, who delivered in a huge way. He added power, he added balance to the lineup, and he settled the middle of the order. Everything kinda came together once Fielder joined the team.

Fielder remained with the Yankees in 1997 but did not have a great season (13 homers and 101 OPS+ in 98 games). He was let go following the season and spent 1998 with the Angels and Indians before retiring. The 1997 season is almost irrelevant at this point. Fielder was brought in to help put the 1996 Yankees over the top and he did just that, especially once the calendar flipped to October.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.