The Yankees have committed to a youth movement over the last 18 months or so, though they’ve done it in a unique way. Sure, they’re bringing up their own prospects from the minors and giving them a chance, but they’ve also traded for young players who fell out of favor with their former teams for whatever reason. Didi Gregorius, Nathan Eovaldi, and Dustin Ackley were all acquired that way. Aaron Hicks too.

The most-notable and perhaps the riskiest such acquisition came at the Winter Meetings in December, when the Yankees shipped Adam Warren (and Brendan Ryan!) to the Cubs for Starlin Castro. Castro’s young and he’s had some very good seasons in his career. The Yankees also gave up a very valuable piece in Warren, someone Joe Girardi called “as big as any pitcher that we have in that room” last October.

The Castro trade was the first time the Yankees gave away a player they’re really, truly going to miss in one of these out of favor trades. Yeah, you could have argued they would really miss Shane Greene at the time of the Gregorius trade, but Greene was not nearly as established as Warren. Warren has been getting big outs for the Yankees for a few years now, and he’s been doing it in a variety of roles. That was a big piece of depth to give up.

Brian Cashman & Co. saw Starlin as too good to pass up, however. He’s 25 years old — Castro turns 26 this Thursday — with strong defensive chops at second base, offensive promise, and a team-friendly contract that can max out at $53M over the next five seasons. Those types of players rarely become available, and when they do, the asking price is usually much higher than an Adam Warren type. Warren will be missed, no doubt about it, but this was a deal the Yankees had to make.

Castro’s first impression has been great — he is 12-for-27 (.444) with two dingers so far this spring — though we all know Grapefruit League numbers don’t mean much, if anything. I guess it’s better than struggling in camp. After the trade Starlin instantly became part of what the Yankees hope is their next core, along with Gregorius, Luis Severino, Dellin Betances, Greg Bird, and some others. What does 2016 have in store? Let’s preview.

So Which Castro Will The Yankees Get?

There’s a reason the Cubs made Castro available. They didn’t trade him out of the kindness of their heart. Starlin’s stock has dipped in recent years because his offense has gone backwards since his promising debut back in 2010. Here is his wRC+ by year. Remember, 100 is league average and the higher the number, the better.

2010: 99

2011: 109

2012: 100

2013: 74

2014: 117

2015: 80

A 99 wRC+ at age 20 then a 109 wRC+ at age 21 is the kind of stuff you see from future stars. Not many players produce at that clip at such a young age, especially middle infielders. Since then Castro has had one league average year, one well-above-average year, and two well-below-average years. He barely outproduced Stephen Drew (76 wRC+) last season.

Last year Castro hit .265/.296/.375 overall, though it was split into .236/.271/.304 (53 wRC+) in 435 plate appearances as the starting shortstop, and .353/.374/.588 (161 wRC+) in 143 plate appearances as the starting second baseman. Small sample noise? Possibly. There were also adjustments made, however. Castro said he worked with Chicago’s hitting coaches to close his stance during his four days on the bench between going from short to second:

“Just moved my front leg,” said Castro to Meredith Marakovits over the winter (video link). “I think my front leg was just too open and I just tried to pull the ball. That’s why at the beginning of the season, I hit a lot of ground balls to third and to short. It’s not the type of player that I am. I just always hit the ball to the middle and right field. The adjustment that I did, I just closed the stance a little bit more and that helped me a lot to drive the ball to the opposite way.”

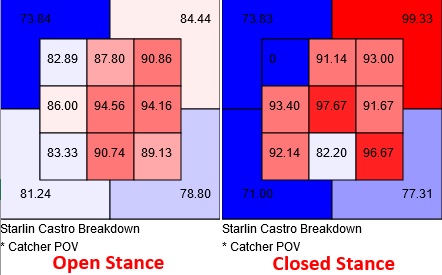

That numbers don’t show a drastic change in Castro’s batted ball direction — he had a 41.2% pull rate with the open stance and a 39.2% pull rate with the closed stance last year, so it wasn’t that big a difference — but he did hit the ball substantially harder. His open stance hard contact rate was 21.6%, which is far below the 28.6% league average. With the closed stance it was a 29.2% hard contact rate, right in line with a 29.1% hard contact rate he had during his 117 wRC+ season in 2014. Here are Castro’s average exit velocities by zone, via the intimidatingly great Baseball Savant:

Starlin was only able to really drive pitches middle-away with his open stance last year. Once he closed it up in August, Castro was able to do a better job pulling his hands in to get to that inside pitch. We have to be aware that this is a small sample of data — again, he only had 143 plate appearances once he moved to second and closed his stance — though for that limited bit of data, Castro closed a hole in his swing on the inner half.

There is also definitely something to be said for having confidence and being comfortable on the field. That can absolutely impact performance. In Chicago, Castro was the guy for a long time. The Cubs won 97 games and were swept in the NLDS in 2008. They won only 83 games in 2009 and missed the postseason. Castro debuted in 2010, a 75-win season, and he was the face of the team’s rebuild. He was the next great Cub, and his success from 2010-11 only added more pressure. That’s a lot to take in at a young age.

With the Yankees, Castro is just one of the guys. Yeah, he’s very important in the long-term, but this season he’s going to hit near the bottom of the lineup and only be expected to help the offense, not carry it. This is a fresh start and of course he wants to impress his new team and his new fans. He’s not expected to be the face of the franchise though. Castro’s coming in with a clean slate and that can be a very good thing mentally.

We’ve seen the raw talent — Starlin hit a ball over the friggin’ batter’s eye last week (video) — and this is a player who is one season removed from a .292/.339/.438 (117 wRC+) batting line. The Yankees would sign up for that in a second. Castro is young, he has natural ability, he appeared to close a hole in his swing late last year, and now he no longer has to be The Man in the lineup. Those are all positives. Last year was rough overall. Now Starlin has a fresh start.

Second Base, Not Third

Cashman talked about trying Castro at third base as soon as the trade was made, though that plan was short-lived. The Yankees pulled the plug before he even had a chance to play a Spring Training game at the hot corner. He did nothing more than work out there in infield drills. That’s probably for the best. Castro is still learning second base, after all. He only played 258 innings there last year.

After spending his entire big league career at shortstop, Starlin said everything felt “backwards” once he moved to the other side of the bag, though he added it only took a handful of games to get comfortable. The numbers at second (+2 DRS and -0.8 UZR) are useless given the sample size, so we don’t have much reliable data. This play from earlier this month …

“(His defense) will be significantly better because of the athleticism and putting Castro at second base, he has the ability to be a very good defensive player. Second base is a little easier for a guy like him,” said one scout to George King. Keith Law also said he would bet Castro is “above-average to plus” at second base. So if nothing else, there are two people on Earth who believe Starlin has the tools for be a real asset defensively on the right side of second base.

There are reasons to believe Castro will be a very good defender at second base, if not right away then in time, as he gains experience. I’m guessing we’ll see a wide range out of plays at second this year. Some truly spectacular plays and some goofs on routine plays, perhaps because Castro is still learning the nuances at second. The early returns at second last season were generally promising, both defensively and offensively. The Yankees want their new second baseman to build on that in 2016.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.