Two weeks ago the Yankees made the most significant commitment to their on-the-fly rebuild when they shipped Adam Warren (and Brendan Ryan) to the Cubs for Starlin Castro. They gave up a cheap yet proven above-average commodity in Warren for Castro, who is owed $40M or so over the next four years. The other rebuild trades didn’t involve giving up players as good as Warren or taking on that sort of financial commitment.

The Yankees are banking on Castro’s youth and talent, which became expendable for the Cubs. Castro had some pretty good years earlier in his career but has been replacement level in two of the last three seasons, so this is a clear risk for New York. They’re hoping his excellent finish carries over to next year. “He really looked like a different player over at second,” said Brian Cashman following the trade.

By now you know the story. Castro started 2015 as Chicago’s everyday shortstop before moving to second base in August in deference to the defensively superior Addison Russell. Starlin hit .243/.278/.320 (59 wRC+) as a shortstop and .339/.358/.583 (154 wRC+) as a second baseman. This could easily be a sample size thing — he batted 443 times as a shortstop and only 121 times as a second baseman — but I truly believe a position change can help (or hurt) a player’s offense.

“The first two games I played (at second base) felt a little bit weird, but after playing three or four games there, I felt pretty good,” said Castro to reporters in a conference call after the trade. Position changes aren’t always easy, but if the player is more comfortable and has more confidence at a position, it could carry over at the plate. The opposite is true too — if he’s not comfortable, it could drag him down offensively. Moving to second may have helped Castro’s bat.

While the position change is a nice story, there is perhaps a more practical explanation for Castro’s improved performance down the stretch: he made some mechanical changes at the plate. Starlin sat four days between the move from short to second, and during that time he worked with the hitting coaches — the Cubs have a hitting coach (John Mallee), an assistant hitting coach (Eric Hinske), and something of a hitting liaison (Manny Ramirez) — to close his stance.

“Just moved my front leg,” said Castro to Meredith Marakovits recently (video link). “I think my front leg was just too open and I just tried to pull the ball. That’s why at the beginning of the season, I hit a lot of ground balls to third and to short. It’s not the type of player that I am. I just always hit the ball to the middle and right field. The adjustment that I did, I just closed the stance a little bit more and that helped me a lot to drive the ball to the opposite way.”

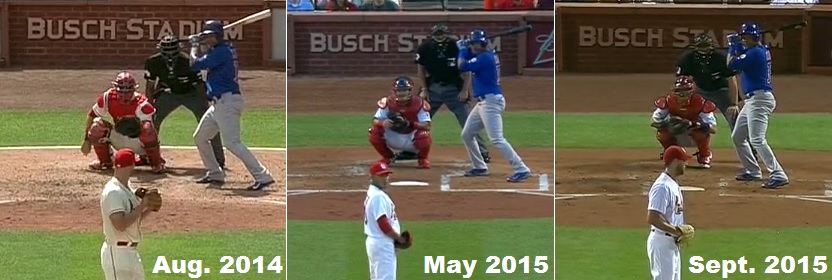

Here is Castro at the plate late in the 2014 season, early in the 2015 season, then late in the 2015 season. You can see his stance was very open in 2014 and early in 2015, but, after sitting for a few days and moving to second, he is much more closed at the plate. (Castro is still slightly open but it is not nearly as exaggerated.) You can click the image for the purposes of embiggening.

“Yeah it’s tough. It’s tough,” said Castro to Marakovits when asked about making the adjustment in the middle of the season. “Especially after six years playing every day, 160 games every year, and then to sit on the bench (for four days) when the team is playing so good. But I don’t want to be selfish. I just put the team first and continued working hard and (tried to take advantage of) the opportunity.”

Anecdotally, it makes sense closing your stance would better allow you to stay on the ball and hit it the other way. Most hitters open their stance in an effort to see the pitch better, but a byproduct can be pulling the ball more often given the direction of the legs and all that. Here is Castro’s batted ball data before and after the adjustment.

| BIP | GB% | FB% | LD% | Pull% | Mid% | Opp% | Soft% | Hard% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open Stance | 342 | 56.7% | 27.5% | 15.8% | 41.2% | 37.1% | 21.6% | 24.0% | 21.6% |

| Closed Stance | 120 | 46.2% | 33.6% | 20.2% | 39.2% | 42.5% | 18.3% | 21.7% | 29.2% |

| 2014 | 430 | 45.3% | 32.3% | 22.3% | 40.2% | 38.1% | 21.6% | 16.0% | 29.1% |

I included Castro’s 2014 batted ball data in there as a reference point for how he hits the ball when he’s going well — Starlin hit .292/.339/.438 (117 wRC+) last year and that’s pretty awesome. That’s the kind of production the Yankees are hoping to see going forward, and the fact his batted ball profile with the closed stance so closely matches his 2014 batted ball profile is pretty rad.

Anyway, the data backs up when Castro told Marakovits, at least somewhat. He did hit the ball on the ground a ton with his wide open stance — that 56.7% ground ball rate would have been the sixth highest among the 141 qualified hitters had he sustained it all season — though he didn’t necessarily pull the ball more often. That 41.2% pull rate is not wildly out of line with last year or what he did with the closed stance. A percentage point or two in either direction is no big deal.

The more important number to me is Castro’s hard contract rate. The league average is a 28.6% hard contact rate, and Castro was far below that early in the season, with his wide open stance. He was (slightly) above league average last year and again this year once he closed his stance. Good things happen when you hit the ball hard, especially in the air. That was the biggest change in 2015. Castro hit the ball weakly and on the ground with his open stance, then hit it hard and in the air with his closed stance.

Now, here’s the thing: I’ve written an awful lot of posts about mechanical changes over the years and more often than not, nothing really comes of it. The only player I can remember who made a noticeable mechanical change and then showed significant, sustained improvement is Curtis Granderson, who went from an okay hitter to a dinger machine seemingly overnight in August 2010. Castro closing his stance can be a whole bunch of nothing.

At the same time, the fact Castro changed his stance and had about a month and half worth of success is encouraging. He’s not an older player trying to stay productive — the vast majority of those mechanical change posts I’ve written were about old dudes trying to hang on — he’s a young guy who lost his way and is trying to get back on track. This isn’t a player trying to compensate for lost bat speed or something like that. Not all adjustments are made for the same reason.

Castro credited Manny Ramirez for helping him this past season — “This is a guy who’s (been through) every moment in the big leagues,” he told Marakovits — and that’s a relationship the Yankees won’t be able to offer, but it’s not like they’re lacking veteran leaders. Starlin’s late-season success is encouraging and the closed stance gives us a tangible reason why it may continue. That doesn’t mean he’s forever fixed, but Castro may have found something that works at this point of his career.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.