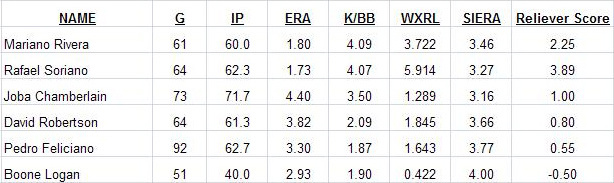

When Rafael Soriano joined the Yankees, the cause célèbre of Yankee bloggers quickly became the use of Soriano as a fireman in the bullpen. EJ Fagan from The Yankee U and our own Ben Kabak have both discussed it recently in detail. In a nutshell, the Yankees now have two closers in Rivera and Soriano. Given that Rivera will pitch the ninth and that the eighth inning isn’t always the highest leverage moment that the bullpen will face, they argue persuasively that the Yankees should use Soriano to put out fires, whether those fires arise in the sixth, seventh or eighth innings. This concept is logical and well-founded, yet I think there’s a good reason to believe that the Yankees, or most other organizations for that matter, won’t employ it in 2011.

It’s no secret that the New York media is unforgiving. While Brian Cashman seems to avoid a lot of the nastiness, plenty of reporters assume a sarcastic and critical approach towards Joe Girardi. Their Twitter accounts during games are rife with jokes about Girardi’s matchup binder, and they seem to enjoy playing “gotcha” with Girardi’s information about player injuries and explanations about decisions. Very simply, an unorthodox idea like using Soriano as the fireman would likely be met with criticism in print, in the airwaves and on the internet. One can imagine the reaction if Soriano blew a lead in the sixth inning and the Yankees lost the game, or if Soriano saved a lead in the sixth but saw Joba Chamberlain surrender the lead later in the game. It’s easy to picture the back page of the New York Post with a gigantic headline like, “Bonehead: Why is Joe Girardi using his $35 million dollar man in the sixth inning?”

Of course there is a very good answer to this question, one built on data, logic and research. But it’s a complicated answer and it doesn’t lend itself to a sound bite. It’s easy to say that Soriano is our “eight-inning guy, period”. It’s way more difficult to explain that the manager is going to try to maximize win probability by utilizing the best relievers in the highest leverage spots. It would also require Girardi to explain why Rivera isn’t used in the highest leverage spots, and only in the ninth inning, a question which would require him to admit that this idea is a bit of a hybrid between the traditional use of a closer and the more sabermetric-inclined concept of leverage and probability. In a media environment not known for kindness, friendliness to new ideas or nuance, one can imagine how badly this would play out. Who’s ready for a summer of arguing with the beat writers!

Of all the reasons not to do something, though, worrying about how the New York media would perceive you has to rank near the bottom. This reason would also be moot, and Girardi wouldn’t be the focal point of the criticism, if it was clearly communicated that he had the full confidence of the organization to execute this plan. As such, whether Rafael Soriano is used as a fireman or strictly in the eighth inning is a question of organizational incentives, a cost-benefit calculation that all relevant actors in the organization have to perform. Traditional bullpen management works well enough. Put another way: traditional bullpen management is orthodox, accepted by fans, media and other organizations alike. There may be a much better way to do it, but no one at the moment seems to be trying it. The potential gain is not losing a lead, something that most people assume as a given anyway. Think about it: in the best-case scenario the team doesn’t surrender a lead that it already has. The downside risk is a bit greater. For one, the team could actually lose the game in question, should the fireman give up the lead. The manager could lose the faith and confidence of the fans, or worse, his superiors. Ultimately it’s at least possible that that the manager could lose his job.

Unfortunately, we don’t have a very good sense of what organizational incentives are like for the New York Yankees. Our knowledge of the inner-workings of the Yankee organization is quite limited. Our first-hand information is self-selected by the GM and the Manager, or comes at times of unrest and dissension (the Cashman-ownership split on Soriano, for instance). Our second and third-hand information is even more problematic. It comes through the conduit of reporters and leaks. Often times one has to wonder whether the information made public is designed to serve some sort of Machiavellian purpose. What part of the organization is leaking this information and why? Are they attempting to undermine another part of the organization? Are they lying in order to throw competitors off the scent? Is this simply good information? But this is about as deep as most fans can go. We simply will not know what Cashman and his cadre of advisors did this winter in secret. We won’t know if they looked at the possibility of a four-man rotation, batting Cano second or using Soriano as a fireman. We won’t hear about the ideas that they entertained, researched, debated and ultimately rejected.

As such we have to at least consider that the concept of Soriano as fireman has been explicitly research and rejected by Yankee management. Yet we also have to consider the flipside, that the organization is more by-the-book in certain areas, and that taking big risks in high-profile situations isn’t encouraged. This would mean that no matter how sound or logical the concept is, the Yankees will never be the first team to adopt it. Ned Yost of the Royals perfectly captured this sentiment yesterday when asked about the concept of a fireman. Kings of Kauffman has the quote:

Yost is still a baseball guy, and there’s a way things are done in baseball and a way to not do things. Innovation isn’t a popular idea. Using Joakim Soria in an early situation might make sense by the numbers “but you won’t catch me doing it.”

This is an unsatisfying feeling and it’s one familiar to anyone who has worked in a corporate environment and found that doing things as they’ve been done in the past and not looking like an idiot is more important than trying to invent new ways of doing things and possibly failing. It’s flat frustrating when the best idea loses out to the more familiar idea. It’s also bad organizational management, because it aligns the interests of the employees with keeping their jobs and not screwing up, rather than allowing a certain amount of room for failure and fostering innovation and productivity. But the Yankees don’t particularly need to reinvent the wheel. They don’t need to discover untapped markets of value like the Rays or the Athletics need to in order to succeed. In New York, where the lights are as bright and as hot as anywhere on the planet and where “what have you done for me lately?” is a way of life, there is little margin for failing and looking dumb.

This summer, Girardi is going to leave Soriano and Rivera chucking sunflower seeds against the plexiglass as a lesser reliever blows a lead. Sergio Mitre may pitch the 13th inning of a tie game on the road while Rivera waits for the team to get the lead before coming in. When this happens, it’s important to recognize that it’s not necessarily because Girardi is thickheaded or stubborn, too smart for his own good or intentionally trying to annoy the curmudgeonly beat writer crew, although the latter would be spectacular. Girardi may be a very public face of the Yankees, the one who projects authority and whose face is on television every night, but ultimately he’s another organizational actor subject to peer pressure criticism from his superiors. What Girardi doesn’t want to become is another Jeff Zucker, who risked job safety and ratings certainty on an unknown quantity with arguably higher upside and long-term success only to have to back out of it when it turned difficult. At that point, Zucker’s fate was written on the wall. It was only a matter of time before the house came down.