By now it is nearly impossible to discuss the Yankees’ search for starting pitching without saying something like, “It’s no secret that the Yankees need starting pitching help”. It’s all been said. Even if Andy Pettitte postpones his date with retirement another year and returns for the 2011 campaign it’s likely that the team could still be looking for help on the trade market this summer. Ivan Nova is a fine fifth starter option, but it would really be nice if he was the sixth starter, an option in case of injury or a terrible outbreak of Bad A.J. The problem is that the trade market is a bit weak. There’s no Cliff Lee on the market this summer. Wandy Rodriguez looked like a decent target, but the Astros just extended him for three years. Gavin Floyd and Chris Carpenter could be very good options, but a lot needs to happen for these teams to put the players on the market. Plan B might be patience, but there’s a fair amount of contingency contained therein.

One trade option is Johan Santana. Mike addressed the possibility of acquiring Santana in this mailbag piece several weeks ago, outlining all the reasons why the Yankees shouldn’t attempt to acquire Santana: he’s coming off major shoulder surgery, his performance is in decline, and he’s expensive. All of these things are true, and yet I’m going to attempt a possibly quixotic reexamination of his desirability. This will be a two part piece. Today we will examine the nature of his injury and his perceived decline over the past 3 years and tomorrow we’ll look at his contract status and try to evaluate whether he makes sense for the Yankees as a trade target. It sounds crazy, and it’s going to take a decent amount of time to make the case. All good things take time though, unless we’re talking about a Chipotle burrito, so try to stick it out with me. It’s not like there’s anything better to do on a freezing weekend in January. What, you gonna watch curling?

Injury

When Johan Santana was injured late last summer it was initially reported that he had a strained pectoral. This was slightly deceiving, in that the location of the injury is not where one would expect. When you hear “strained pec”, you think about how sore you feel if you do too many bench press sets. As Will Carroll noted, the strain happened right where the muscle inserts into the humerus, just below the shoulder. You can see the picture here. Despite initial good news out the Mets camp, which cruelly raised the hopes of Mets fans, it turned out that Santana’s injury was far more serious. Santana had torn the anterior capsule in his left shoulder and required surgery to repair it. The injury is more rare than a Tommy John surgery, and Carroll went to sources to get more information about the actual nature of the injury:

The anterior capsule is the front lining of the shoulder joint which then attaches to the labrum and then to the bone. The capsule is torn with the labrum often with an acute traumatic shoulder dislocation. However, in baseball with repetitive throwing the anterior capsule can just gradually stretch out and eventually give a thrower pain and a feeling of weakness and a velocity loss. This repetitive microscopic tearing and stretching injury ultimately is what the thrower may describe as a “dead arm” The type of surgery performed is very similar to the open surgery pioneered by Dr. Frank Jobe that was performed on Orel Hersheiser in the ’80s, but now with advances the same surgery can be done arthroscopically. However, the healing concepts are the same and therefore the rehabilitation can be very long to get back to high level throwing. Certainly 6-9 months is not unreasonable.

In order to repair this injury, the surgeon usually attempts to repair the ligaments arthoscopically. This was Dr. David Altchek’s goal with Santana, but he found that the tear was difficult to reach with an arthoscope and had to make an incision in the shoulder in order to repair it. This is obviously a less desirable method because it causes scar tissue, which can affect range of motion and lengthen the time of rehabilitation. As such, Santana may not return to the majors until the All-Star Break in 2011. The final word from Carroll:

Santana will immediately begin rehab which is normally tagged at 20-28 weeks with an overlap of a throwing program towards the end. There’s no new info on whether there was anything found during the procedure that would change the outlook or prognosis. The first real sign we’ll get is likely to be when pitchers and catchers report to Port St. Lucie in February.

There is some speculation that Santana would not be fully recovered until well after he actually returns to the majors. Dr. Craig Levitz speculated that it would actually take 3 months, or 70-80 innings, after Santana’s return for him to regain his top form. He also noted that pitchers with this type of injury often return stronger than before, and that there is little risk of recurrence. As Levitz said, “Over all there is not a lot of damage to the shoulder with this injury…Once they close the hole in the soft tissue, it should never be a problem again.”

Performance

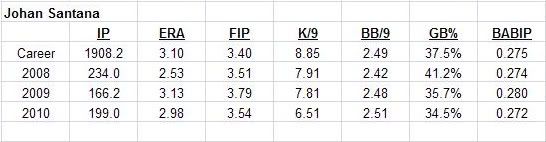

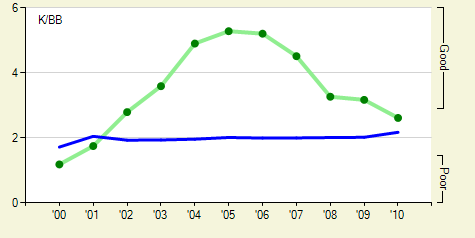

Things have been different for Johan Santana since he left the American League for the National League Mets. From 2002 to 2007 he had an ERA of 2.92, striking out almost 10 batters per nine innings and walking 2.2 per nine innings. His strikeout to walk ratio was a Lee-esque 4.38. Due to a very low hit rate, Santana’s WHIP hovered around 1.00. For good reason he was considered one of the preeminent pitchers in all of baseball. Contrary to expectations, Santana’s strikeout rate has dipped about two batters per nine innings since joining the Mets, and his walk rate has increased ever-so-slightly to close to 2.5. As such, he’s posted FIPs in the mid 3.50s since coming to New York, certainly respectable but not exactly the commensurate with the highest expectations fans might have had for the well-paid ace. This chart shows his performance as a Met compared to his career numbers:

Peripherals-wise, 2010 was Santana’s worst year. This is to be expected, given that he was coming off minor elbow surgery from the offseason prior and had his season cut short by the shoulder injury in September. One thing we don’t know is to what extent Santana pitched through discomfort or pain in 2010 before acknowledging his injury. We also don’t know if the gradual destruction of his shoulder ligaments was responsible for the decline in performance. The quote from Carroll’s source above seems to confirm that the pitcher will likely experience discomfort, weakness and a loss of velocity before actually needing surgery to repair the injury. It would be logical to expect a bounceback in velocity and strikeout stuff, but within any injury there is a large amount of risk and variance. It all hinges on how well Santana heals.

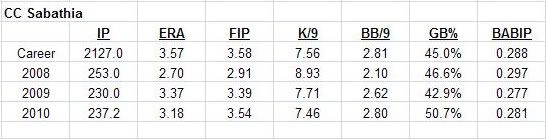

Despite the decline in performance, Santana was still a very valuable pitcher for the Mets in 2010. As a quick and easy comparison, his 3.5 fWAR in 199 innings in 2010 ranks similar to Shaun Marcum and Wandy Rodriguez’s performance. Over the past three years, despite an injury-shortened 2009, he’s accumulated 11.0 fWAR. This is more than Andy Pettitte, James Shields, John Lackey or Ted Lilly. If he had thrown 200 innings in 2009 it’s likely that he would register more fWAR in the past 3 years than Matt Cain, Roy Oswalt or Javier Vazquez. Of course, he didn’t throw 200 innings in 2009, so the point is moot. Regardless, Santana is still a valuable pitcher. Compare his performance data above with this data for CC Sabathia:

Sabathia and Santana both have fairly similar FIPs and ERAs, but Santana seems consistently able to outperform his FIP. They also have similar strikeout rates. Sabathia’s walk rates are slightly worse than Santana but CC generates far more groundballs than Santana, a clear boon in Yankee Stadium. Santana’s flyball tendencies play well in Citi Field but would likely be less advantageous in another venue. Sabathia’s numbers are also more impressive in the AL East. All things considered, Sabathia is a more desirable starter, but simply because Santana isn’t replicating his same level of dominance from years past doesn’t mean that he’s no longer valuable. Mid-3 FIP pitchers with good control and strikeout stuff don’t grow on trees.

Johan Santana isn’t what he once was, and he’s coming off a major injury with a long rehabilitation timeframe. There are good reasons for optimism though, reasons that don’t solely consist of fluff and happy thoughts. If Santana can pitch again like he has as a Met, he’ll have good value for his team. Of course, there’s the whole question of the contract, a question which I’ll address tomorrow morning before trying to ascertain how the trade market could firm up. See you then.

I thought that once Johan was dished to the Mets, we’d kinda stop talking about him. We had some

I thought that once Johan was dished to the Mets, we’d kinda stop talking about him. We had some